He has liberated his own mind by confronting the absurdity of his situation, and can view it with the appropriate contempt and good humour. In a sense, he is ‘free’: not from having to perform the task, but from performing it unquestioningly or in the vain hope that it will end. When Sisyphus sees the stone rolling back down the hill and has to march back down after it, knowing he will have to begin the same process all over again, Camus suggests that Sisyphus would come to realise the absurd truth of his plight, and treat it with appropriate scorn.

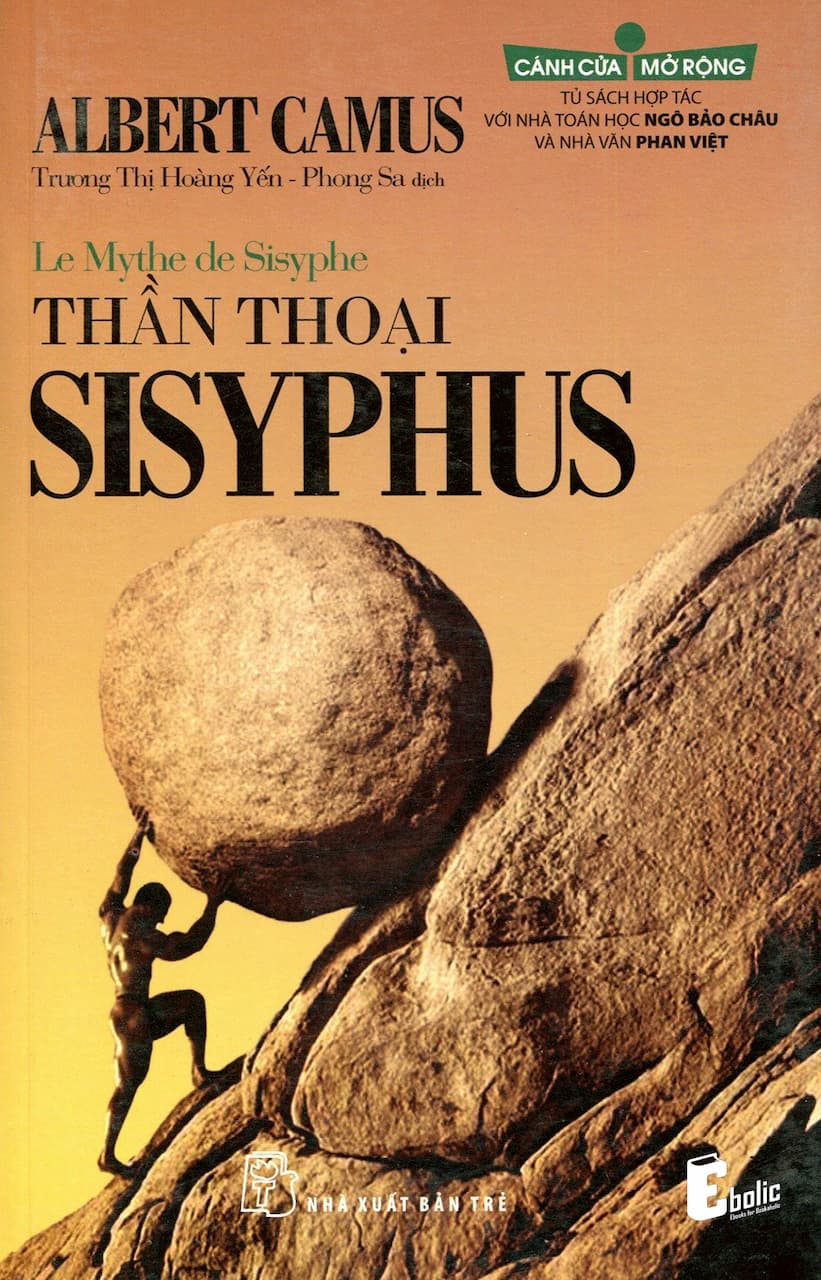

However, for Camus – and again, this part is generally misunderstood by people who haven’t read Camus’ essay but only heard about its ‘argument’ at second hand – there is something positive in Sisyphus’ condition, or rather his approach to his rather gloomy fate. Such is the life of modern man: condemned to perform the same futile daily rituals every day, working without fulfilment, with no point or purpose to much of what he does. The story of Sisyphus is so well-known in modern times thanks to Albert Camus, whose essay ‘ The Myth of Sisyphus’ (1942) is an important text about the absurdity of modern life (although it’s often described as being ‘Existentialist’, Camus’ essay is actually closer to Absurdism).įor Camus, Sisyphus is the poster-boy for Absurdism, because he values life over death and wishes to enjoy his existence as much as possible, but is instead thwarted in his aims by being condemned to carry out a repetitive and pointless task. You really can be too clever for your own good: Sisyphus was. Not all Greek myths have a ‘moral’ as such, but it’s clear, when we look at a fuller summary of the story (or stories) of Sisyphus, that his punishment – rolling that rock endlessly up a hill – was contrived by the gods in response to Sisyphus’ legendary craftiness and cunning.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)